Singapore has achieved astounding economic success

Can Lawrence Wong, its incoming PM, oversee further growth?

Your browser does not support the <audio> element.

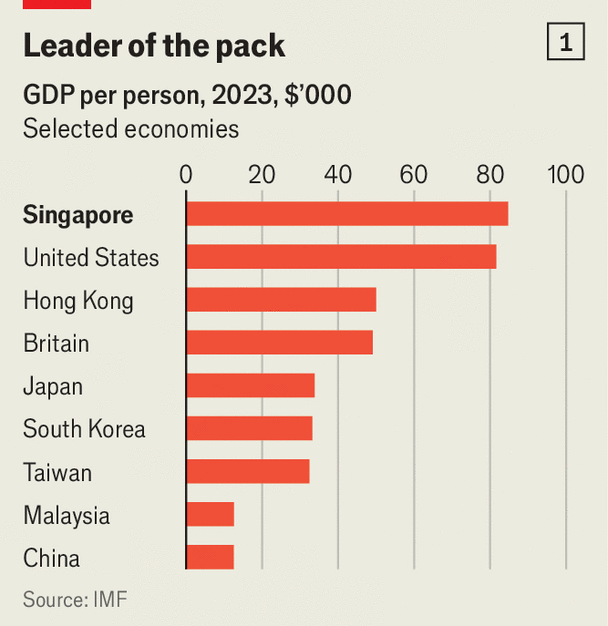

Since its independence almost 60 years ago, Singapore has become a beacon of prosperity. In a part of the world where middle-income status is the norm, the city-state is now the richest country for many thousands of miles in any direction. At around $88,000, its GDP per person has doubled in real terms over the past 20 years. At the moment of its independence in 1965, the country was poorer on the same basis than South Africa or Jordan.

But as the world looks at globalisation with increasing scepticism, balancing Singapore’s domestic politics against its role as a global city will become trickier. “The established norms are eroding,” says Lawrence Wong, Singapore’s incoming prime minister, speaking to The Economist on May 6th. “People are searching for new bearings, but the new order is not yet established. I think it will be messy for quite a few years, maybe a decade or longer.”

By any measure the country’s economic record is impressive. During the past two decades, the median wage for Singaporean residents in full-time work has risen by 43% in real terms, compared with an 8% rise in America. At around $46,000, the median full-time wages of Singaporeans are now higher than those in Britain, the country’s former colonial boss, where they sit at around $44,000.

Singapore’s stature as a financial centre has risen in recent years, leading to inevitable comparisons with Hong Kong, once the undisputed leader among Asia’s global cities. Indeed, the country seems to be outstripping its rival. The city-state maintains a solid lead in salaries, which are around 50% higher for Singaporeans than Hong Kongers. As a hub for wealth it is growing far faster than its competitor: in 2017, Singapore boasted $2.4trn in assets under management, according to the Monetary Authority of Singapore, about three-quarters the size of Hong Kong’s $3.1trn. By 2022, Singapore’s pile had grown to $3.6trn, just 8% behind Hong Kong.

Despite Singapore’s growing success as a financial centre, policymakers do not crow about its success. They fret rather than cheer about the idea of Hong Kong’s erosion as an international hub. In 2019, during Hong Kong’s massive pro-democracy protests, the Monetary Authority of Singapore struck back against reports that the city was the beneficiary of capital flight from Hong Kong. Even so, as a result of Hong Kong’s weakened reputation, Singapore has become more important as a hub for Chinese wealth.

It is not just the private sector’s holdings that have bulged. Singapore’s state-owned investment company, Temasek, had $287bn in assets as of March 2023. The country’s Monetary Authority manages around $369bn in foreign-exchange holdings, gold and other reserves. Singapore’s GIC, previously known as the Government of Singapore Investment Corporation, does not disclose its holdings, which the government only concedes are above $100bn. But by the estimates of Global SWF, a data firm, the GIC’s assets are the largest of them all, running to $769bn. If correct, that would make the sovereign wealth fund the sixth-largest in the world, outstripped only by a handful of petrostates and by China’s two funds. It would also mean that Singapore’s state-owned assets run to over 270% of its GDP, an enormous hoard.

These large sums illustrate an economy that saves far more than it spends. Singapore also has one of the largest current-account surpluses in the world. As a small country and a close partner of America in security, Singapore avoids the scrutiny others might endure for its huge savings and managed exchange rate. The fact that America has a bilateral trade surplus with Singapore tends to keep it out of the glare of protectionist American politicians. But the country briefly landed on America’s watchlist for currency manipulation under the administration of Donald Trump. If he triumphs in November’s election, Singapore runs the risk of returning to the crosshairs of America’s trade warriors.

International opprobrium is a less immediate concern than domestic pressure. Since the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) won 83 of the 93 seats in the Singaporean parliament in 2020, it would be easy to presume that it has little to worry about from the opposition. But the clutch of seats held by the centre-left Workers’ Party is the largest presence for another party in parliament since independence. Before 2020 there was no leader of the opposition in Singaporean politics. By the standards of a Western democracy, the dominance of the PAP is still overwhelming. But the presence of competition has changed the calculus: it has made the government more focused on public consultation before pulling the levers of policy.

The opposition has different views on how the city-state should be run. Its lawmakers have called for a higher share of the returns on the assets to be remitted to the budget and used for everyday spending, rather than the 50% currently permitted. They also argue for greater transparency when it comes to the make-up of the reserves and the total held by the GIC.

The government reckons the idea of putting the reserves at risk would be a sop to populism. It argues that the country is ageing, and at its present income levels it will never go through a similar period of rapid growth as when the assets were accumulated. The bull markets which produced strong returns for riskier investments, like Temasek’s 20-year returns of 9%, may never be so favourable again.

Strait and narrow

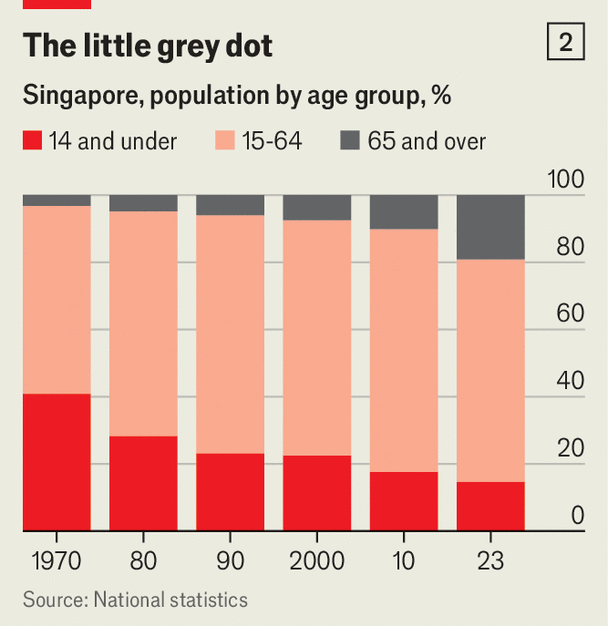

But the cost to Singapore’s public finances as the country ages will have to be funded somehow. The proportion of Singapore’s citizens who are over 65 rose to 19% last year, from 12% a decade ago. It will rise to almost 25% by the end of this decade. Social spending has roughly doubled in the past decade, and state spending on health care now outstrips the education budget. Singapore’s low level of government spending, the envy of small-state advocates the world over, is climbing: it will reach 20% of GDP by 2030, from 14% in 2010. Tax increases are likely. A sales tax has already risen: the levy has climbed from 7% to 9% in the past two years.

Meanwhile the country’s changing demography will make itself felt in other ways, too. In 2023 Singapore’s fertility rate fell to just 0.97, a figure below all but a small handful of countries in the world. The Singaporean government does not publish detailed population forecasts regularly, but UN projections suggest that without immigration Singapore’s working-age population would drop by a third between 2022 and 2050.

Immigration is controversial in Singapore. The share of the city’s population made up of its own citizens has dropped from 74% in 2003 to 61% last year. The city has four official languages and three official ethnic groups, of which Chinese are by far the largest. The government tries to keep this balance. Ethnic Malays, who are mainly Muslim, are a minority in Singapore but a majority in Malaysia and Indonesia, its far larger neighbours. So Singapore’s restrictions on speech are tightest where religious and racial sensitivities are touchiest. Even for a political force as dominant as the PAP, high levels of migration seem a political threat.

Mr Wong notes that Singapore will continue to need foreign workers. “We welcome foreign professionals to work in Singapore, but it’s controlled, because if it’s not controlled I think we will be easily swamped,” he says. “We cannot afford to be like the UAE, where the local residents are only less than 10% of the population.” He says he could not imagine a situation where Singapore’s citizens are a minority.

Balancing the needs of big international companies and Singaporeans’ wariness of immigration will be an increasingly delicate task for the government. In a survey published in 2021 by the Institute of Policy Studies, a unit of the National University of Singapore, 44% said that immigration increases unemployment, a figure that rose to over 50% among respondents over 65.

However, the greatest of all the threats to Singapore’s enviable position are those outside the control of the city-state. It sits on the Strait of Malacca, a bottleneck for trillions of dollars in global trade. Its trade volumes run to an enormous 337% of its GDP, compared with 27% in America and 68% in rich countries across the world.

The fraying of relations between Beijing and Washington is a particular worry. Singapore is heavily exposed to both countries. In the worst-case scenario, in which trade is split between two global blocs—between those countries which voted to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine at the UN General Assembly in 2022, and those which did not—Singapore’s GDP would decline by around 10%, compared with 3% for Asia or 1% for the world.

China is not only Singapore’s largest source of imports, as it is for most countries in the world, but its largest source of exports too. Almost all East Asia’s energy imports flow through the Strait of Malacca, and much of its manufacturing trade flows the other way.

Geopolitical dot

At the same time, America remains by far the largest single investor in Singapore, with S$574bn ($428bn) invested in the country at the end of 2022, compared with 156bn from mainland China and Hong Kong combined. According to the American Chamber of Commerce in Singapore, American firms employ over 200,000 people in the country, about 6% of the workforce. Singapore is also America’s closest security partner in South-East Asia, despite its neutral diplomatic stance.

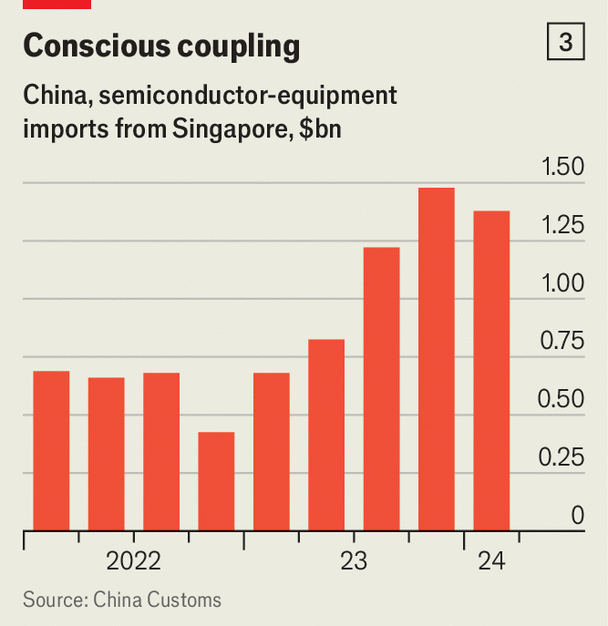

America’s increasing restrictions on China’s semiconductor industry could embroil Singapore in the spat between the two countries. Its chip industry does not specialise in the most advanced nodes, where Taiwanese firms predominate. But it does well in producing older chips, known as mature nodes. America’s Department of Commerce has said it has no plans to extend its restrictions and sanctions to older chips. But China’s massive expansion of its legacy chipmaking may change that. In the second half of last year, Singapore’s chipmakers sold around half a billion dollars’ worth of equipment a month to China, a figure that is more than double the same period in 2022 (see chart 3).

Mr Wong says the government recognises America’s prerogative in export restrictions where national security is concerned, but hopes they are carefully calibrated. Jake Sullivan, the national security adviser in President Joe Biden’s administration, has spoken of a small yard with a high fence, referring to controls imposed on a small number of high-tech industries. “If you start expanding the yard,” Mr Wong says, “and the yard keeps getting bigger and bigger...I think that will be detrimental not just for Singapore but for the US and for the whole world.”

For the country’s anxious bureaucrats, the idea of planning for a full-scale split between America and China is a ghastly prospect. Singapore hosts the global headquarters of TikTok. In January its CEO, Shou Zi Chew, a Singaporean, was grilled by American lawmakers, who even asked him if he had applied for Chinese citizenship, or had been a member of the Communist Party of China. Clips of the questions, and Mr Shou’s befuddlement, went viral in Singapore and abroad. It showed how hard it is to straddle the two worlds.

Of all the varied economic risks facing Singapore, one underpins the lot—and bugs the city’s watchful administrators. What happens if Singapore, like Britain or other slow-growing European countries, entered a period of stagnation in which ordinary household incomes stop rising? That sort of pressure would threaten the contract between the PAP and the Singaporeans, who vote for them in extraordinary numbers in the expectation that they will continue to get richer.

Before November next year, Mr Wong will lead the PAP to a general election, the results of which will frame his time in office. Singapore’s successes give its new government a great deal to preserve. Few countries have managed to surf the wave of globalisation so competently. With the tide now quickly going out, Singapore faces its greatest challenge. ■

Explore more

This article appeared in the Asia section of the print edition under the headline “The view from the top”